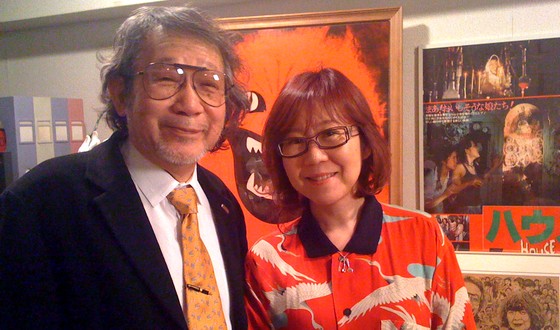

INTERVIEW WITH

NOBUHIKO OBAYASHI

“When I was a kid, I found lots of photos and picture books from foreign countries in a back shed. I really liked those beautiful pictures, and wanted to shoot something like them in a film”

A popular figure in the world of Japanese cinema and television, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s career spans more than 50 years. While mainly known for the unique horror film House, Obayashi’s filmmaking journey has been just as unusual — from commercial cinema to auteur theory to experimental realms, he has done it all. One such field for which Obayashi has had the most success has not been touched on enough in the West — advertising. In this realm, he's a pillar and innovator, creating many colorful moments where tenderness, irony and malice alternately appear in his recognizable style, leaving a definite mark on Japanese television and pop culture. Obayashi unveils this unrecognized facet of his life to us here. How did you get involved in the growing cultural movement in Shinjuku at the beginning of the 1960s? | |

We had just started shooting on 16 mm film in those days. Well, when I had been shooting 8 mm film, Kinokuniya Hall opened. There was only Sogetsu Hall before that [1]. Kinokuniya Hall had been showing 16 mm experimental films that used jazz sounds matched by the artist: writer Shintaro Ishihara, poet Shuntaro Tanikawa, anime artist Youji Kuri, and musician Naozumi Yamamoto, etc. To us, their films looked top notch. That was why we started using 16 mm. In those days, after Kinokuniya Hall opened, we started calling ourselves “film artists” because that sounded cooler than movie director. I felt opposition toward the Eizo-sedai (image artists of the generation) at that time. I took objection to the Eizo-shugi (visual images of film) like Toshio Matsumoto espoused. It was different from what I wanted [2]. | |

Anyway, I didn’t feel that I was a movie director. I made my name card for the first time when I was 20-years-old and it read “movie artist.” The first time, I put “movie maker,” but I thought it was weird, so I changed it to “movie artist.” I still live by it. I think it was around the time that the Yomiuri Independent [3] closed doors—Takahiko Iimura, Youichi Takabayashi, and myself—established the Film Independent. But three of us weren’t enough. We called Matsumoto and Youichi Higashi from a group of documentary filmmakers. Even more people were called up, including Genpei Akasegawa and Yoko Ono, musician friends of Iimura. Since an 8 mm film image can’t be captured well on a big screen, we needed to start shooting 16 mm film instead. I shot Complexe at that time (1964). | One day the staff of a TV commercial project contacted us. Since the TV commercial wasn’t considered a creative medium at the time, they approached us only for the reason we were shooting on 16 mm film. Actually, none of us had ever been involved in the commercial film field. I don’t think Takabayashi did one at that time. Iimura took on one that was a medicine commercial, but when we saw it, we felt sick (laughs). He said, “It isn’t cut out for me” and quit. Eventually only I kept taking them. Did the staff from Dentsu (the advertisement agency) approach you because they got wind of you doing something intriguing? |

According to what I heard, there was really a call out for experts for the field of commercials. Commercials were considered a chindon-ya (a Japanese band of traditional musicians hired to play music in front of a newly opened business) at that time. See? It’s a discriminatory term. In short, artistic expression had to include your philosophy around that time. Well, the most symbolic artists back then were these girls who were selling their own poetry books in Shibuya, which were called "My Poetry". They mimeographed them themselves, and it was a status symbol, a way of self expression. Since movies didn’t have that kind of status yet at the time, those girls achieved a feeling of superiority. TV commercials didn’t have any artistic theme. They were just an advertisement for selling products. Since Shin-Toho studio closed around that time [4] , many movie directors had nothing to do. However, it is said that when the staff at Dentsu tried to approach them, they kicked them out saying “Don’t be rude! Are you gonna make me a chindon- ya ?” | The staff at Dentsu had to slip in through the backdoor of their client companies to make their TV commercials—and they only got to eat a bowl of rice with two pickles and a piece of baked salmon at their cafeteria. They came up with the idea that clients might be more welcoming if those commercials had a director. But when they asked directors, nobody took them up on it. This is why they finally approached us. Since we were shooting 60 or 120 second films at that time, they assumed that we might take the chance and shoot a commercial due to shortage of money. |

| Zatoichi goes pop ! | I still remember the day vividly. They said: “We are from a company named Dentsu, and we’d like to ask you to shoot a commercial” and then they stepped back two or three yards—and this might be over-exaggerating—the three of them did it at the same time. They thought they would be kicked out. They looked as if they were begging “please don’t kick us out.” Takabayashi and I said, “We are not that violent.” Well, Iimura seemed like he was about to kick them out, though. We heard that they wanted to hire a director for a commercial. Takabayashi turned them down saying he couldn’t express anything in 60 seconds or 120 seconds in a commercial. Iimura didn’t care about it at all, so I answered “I’ll take it.” |

I thought that it would be great to shoot on 35 mm film, even if the commercials didn’t have any real artistic merit. I had shot an advertisement on 35 mm film for a shopping mall. My wife and I acted and directed for it as Jack and Mary. A friend of mine played Robert. It was always Jack as the main character, Mary as the woman, and Robert as the rival in silent cinema in old Japan. The three characters hung out around Soshigaya-Okura, Kyodo, and the Shimokitazawa area [5] introducing the shopping mall there. The background music was always Offenbach’s Orphee aux enfers when it was a chasing scene and Schuman’s Träumerei when the scene had a happy ending. Tenkosei (Exchange Students, 1982) is rooted in this. I expected my films would be better if I did it more professionally. I always think shooting a good image is important. Even if it doesn’t have any artistic theme, if the image shows beautiful art, it can be a good work of art. When I was a kid, I found lots of photos and picture books from foreign countries in a back shed. They were all in color, and we didn’t have those in Japan around that time. I really liked those beautiful pictures, and wanted to shoot something like them in a film. We were called film artists, so I thought shooting an artistic commercial was a job for us. This is why I started working for Dentsu. | I assume that you were offered equipment, materials, and a budget that you personally had never used before, right? |

I got 2,000 yen for the first commercial film. The second was 4,000 yen. The next was 8,000 yen. The next was 20,000 yen and then 40,000 yen after that. This rise was within only two months time. At that time, it cost 1,000 yen for a 1-jo boarding room [6], including two meals. A 4.5-jo room cost 4,500 yen, and a 6-jo room was 6,000 yen. It was stated that the starting salary for a university graduate was 8,000 yen per month, 12,000 yen per month for a Tokyo University graduate, and I was making 20,000 to 40,000 yen. I lost a sense for the value of money. At that time, we thought that receiving money from artistic work was something to be ashamed of. It was said that the value of true art was supposed to be accepted 100 years after the artist was dead. To us, shooting film was one type of art, so we felt that we shouldn’t have received money from it. We didn’t really take money from Dentsu because of this reason. Well, there was one more reason why we didn’t want to receive the money from Dentsu. When we went there, debt collectors from hostess bars were waiting there, too. We had to wait half a day to get the money there. See? Waiting for money along with debt collectors was something that was not an artist’s business. | Companies posted an advertising budget that technically got higher and higher, but actually we didn’t receive a thing from them. Even though we worked for free, we were happy to be allowed to use the huge stage that Toho didn’t use anymore. We sat in Toho almost every day. Some of the Toho staff, who we had come to be friends with, saw our set and said, “Looks like Hollywood!” Not just the set—we had also brought over various film development techniques from foreign countries. You might say that those techniques were improved by commercial film staff like us at that time. When the staff at Dentsu approached movie artists, who else responded to them? None of them took on shooting commercials except me. Their main building was a two-story wooden one at that time. I saw Akira Odagiri for the first time there, who ended up becoming the head of the agency, and led the Japanese commercial field. He was the same age as me. He took me to the set of the commercial he was shooting at the time—a commercial that stated by sending the bottle cap of the product, you get a chance for a free gift or something. It was obviously an amateur’s. (laughs) I said, “Let me do it.” My work was on the air for 10 years. I was captured by Dentsu after that. I thought I would have done only one or two films, though. They paid anything for it. Furthermore, at that time, the good part was that you could shoot whatever you wanted to if you showed the product for five out of the 60 seconds. Generally, a TV commercial was 60 seconds at the time. The longer ones could be three minutes, the shorter ones at least 45 seconds. |

| A commercial re-used in Confession (1969) | Only five seconds was okay? Yeah, sure. It was just like my private movie with a sponsor. Today it sounds weird, but you have used parts of those commercials for your movies, too. Yeah, if you did it now, it would be a copyright problem. Nobody cared back then. I believed that even if it was a commercial, it was shot by me, it was mine anyway. It wasn’t considered a problem at that time. When I screened my work and invited those companies, they were glad to see it, saying “there’s our commercial.” So, even if you could use 35 mm film and got a high budget, nobody wanted to do it? A new generation who would take money without being ashamed came out around that time. I couldn’t understand them, though. They started working in the commercial industry, and made some companies bigger. People in our generation would think when we got that much of a paycheck for films, “What should we use this money for?” Eventually, we formed a group of about 30 people and hung out in various places all the time. For us, hanging out was part of work. Before starting a shoot on location in foreign countries, we always went and hung out in Izu in the summer, Hokkaido in the winter. About 30 of us would spend one or two months there, with about 20 actors with us, too. The staff of Dentsu or Hakuhodo (another advertisement agency) would come there to ask for a new commercial. The concept of storyboarding had come out around that time, but I didn’t create any. I shot two or three commercials in a month, edited them, and delivered them constantly. I felt like I was shooting my own films with sponsors. Did you occupy the director’s position because you had the most initiative? Yeah, in the way I shot films. I shot about 2,000 commercials, and only prepared about three storyboards. I just shot on the spot even when we went to foreign countries. When we shot on location in foreign countries, we went over with four or five people. We drove a van and located good places, like some nice winery or good scenery spots, etc. We visited them, and if we felt that it was a good place, we stayed there for a month or so and shot four or five films, editing them after we came back. During our busy period, we shot seven films per month constantly. We didn’t have Christmas or New Year’s holidays at that time. The film lab and Dentsu didn’t have them either. The staff at Dentsu worked until midnight on December 31st, and took just a half day off on the first of January. Then, we’d get together after that to receive the New Year’s gift of money from the company president. We were happier shooting films than taking days off. We enjoyed enough of the years of high economic growth. We did whatever we wanted and other people paid for it. Did you learn a lot technically by constantly shooting so many films? We started shooting on location in foreign countries around 1965. It was really fun to go to studios and film labs in foreign countries. We needed to have 1000W lights even if it was daytime. It was very dark in Europe, so I was curious and went to the film lab. They had to apply six or eight times the sensitivity. It was no more than twice the sensitivity at the highest in Japan at that time, but it was eight times in Europe. The same film, but the sensitivity was increased. We learned various ways of developing. For instance, before shooting, by exposing the film for a second, you would get a sepia-colored image like in Italian movies. It was called “flashing,” you know? There would be some brand-new expensive film, and our assistant had to expose it for a second. It all depended on him if we lost the film. Nobody knew if we got it until after coming back to Japan and developed it. We were thrilled so much, so it was fun. If you didn’t get it, you couldn’t shoot the same thing again. Yeah, we made that kind of mistake a lot. Not only our team, but others as well. The fact that the film didn’t show anything when we checked it after coming back happened all the time. Unlike video cameras now, at that time, you never knew until the film was developed. It was exciting anyway, though. |

A ghostly Catherine Deneuve | |

When I went to America for the first time, I went to Hollywood. I experienced going inside a hotel room while wearing shoes, going to bed still wearing shoes. That was in 1965. Since Hollywood Boulevard was so pretty, I felt sorry for walking on the street in my filthy shoes, so I took them off, and walked with my socks on. But, I couldn’t buy new shoes. It was allowed that we bring only 100,000 yen at that time. The rate for one dollar was 360 yen. I only had about 200 dollars that was part of the production costs as well. “We have to walk with socks on,” I said. Believe it or not, I saw then for the first time what patent leather shoes looked like. They were shiny. I saw Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin with women there wearing those shoes. There was a shop named Dino. I think it was around that area. I found a sign with “Obayashi” on it. It said, “Better than Doris Day, Japanese Underground Movie.” [7] That explained it. We had had exchanges with the staff there. Also, I had heard that some movie distribution companies were buying our 16 mm films and bringing them to America to show. So, I felt like, oh, that was the place. |

Our films were showing in San Francisco, too. I never dreamed of shooting Toho movies because I had been seen as a film artist already, and our films were in the center of Hollywood “Better than Doris Day.” So, the reason why I started to shoot movies on the set of Toho was not because we promoted ourselves to do it or wanted to do it. Toho made us the offer. When they saw that we shot what we wanted, they said, “If you shoot a movie it might be like Jaws.” Nevertheless, only employees of Toho could shoot movies at that time. I couldn’t shoot one. Well, I asked my daughter, “If I could shoot movies, what movie do you want me to shoot?” She gave me some of the ideas for House. I wrote the ideas on a piece of paper, and gave it to the staff at Toho. The idea went through right away, but they couldn’t find anyone to do it. The directors at Toho thought it was too absurd.

|

|