Shina in Wartime Japan

The Cinematic Portrayal of Sino-Japanese Relations in the Early War Years 1937-1940

Were Japanese films produced during World War II just unthinking

propaganda? This feature argues that nothing could be further

from the truth. Japan's relationship with and attitudes towards

"Shina" [1] were complex and often contradictory. In grappling with the

entirety of “Shina” –which the Japanese army seemed to overpower so

rapidly – Japanese cinema began to reflect an ambivalence towards the

land it now occupied and the people it ruled over, an unease that

would continue to grow in tandem with the deepening of its

understanding of the continent and the causes of war.

| Films takes on the incidentWaking up to War |

The summer of 1937 was hot and miserable for the film industry in Japan. Cinemas were dominated by films from Hollywood and Europe, the lack of original content had deprived the domestic film industry of a true Japanese hit all year. Ticket sales were slumping, theatre-owners struggling to recoup their losses. Box office receipts of the top six cinemas fell from 10,000yen in the first week of July 1937 to barely 6,000yen the next, putting the majority of cinemas in the red. “This was a week when no customers came no matter what we tried,” cried theater-owners. Kinema Junpo, the leading film weekly, pronounced this “a grim situation for movie theaters” [2]. | |

All this changed almost instantaneously with the breakout of hostilities between Japan and Chinese soldiers at Marco Polo Bridge on the 7th of July, 1937. War was manna to a film industry thirsty for ideas. Just as it is today, war is news, and news means business for the mass media. The news industry was the quickest on its feet to respond, sending camera crews they had already based in Manchuria towards the battlefield within days. On the 12th of July, the six major news companies (including Asahi Shinbun, Yomiuri Shinbun, Osaka Mainichi Shinbun and Tokyo NichiNichi Shinbun) paid a visit to the War Ministry’s news headquarters, where they reached a mutual agreement to “screen news films as fast as possible in movie theaters in order to ensure correct public perception of the war.” [3] Two days later, a similar meeting was held again with the news film representatives, but this time it was called by the Foreign Ministry’s Public Affairs department. According to Manago Heita, Tokyo Asahi News’s representative, the ministry lambasted the film industry for its passivity to date in conveying the cabinet’s policies, and urged them to work together as one for the war effort and actively communicate the war to the public [4]. The three main film companies, Shochiku, Nikkatsu and PCL (soon to become Toho), were not about to stand by idly either, and announced their intention to produce “military films” capturing the entire public spirit and interest in events in Northern Shina. Shochiku, then the largest film company, announced it would establish a production department specializing in military films [5]. | The Rise of News Film |

News film was the clear victor in the early months of the war, leaving the major film studios trailing in their wake. The news film companies were the quickest on their feet in responding to the war, and the first to capture live footage of the frontline and screen it back home. Taking advantage of a special express passenger flight between Tianjin and Tokyo (with refueling stops in Dalian, Seoul and Fukuoka) that had begun operating several days before the war broke out, news companies were able to process film negatives by 5pm on the very day they had been sent. Although it generally took three days for the negatives to be processed, edited, sound recorded, and submitted to the censors, there were also instances of breaking news where news clips were shown unedited in theaters the following evening after arrival [6]. The first edition of “The Northern Shina Incident” was released on July 14th, 1937, and by the next day, theaters around the country had begun screening news films on a daily basis, with some even screening several a day. | Although news film had been used to report on major events from the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, the prohibitive cost limited the frequency of productions and screenings. Produced by the major newspaper companies, they were the forerunner of today’s television news broadcasts. But earlier generations of news film broadcasts had limited accessibility. During the Manchurian Incident in 1933, for example, news films were used to communicate developments in the war to the public, but these were limited to one-time exhibitions in city parks, public halls, schools, or outside train stations. But in the following years, movie theaters began to include news films in their regular programming, transforming news film into a media commodity to be consumed just like newspapers or magazines. But it was with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident that the demand for news film exploded and the genre underwent significant transformation. |

The success of news film was undeniably linked to its extensive coverage of the war. Long lines formed outside movie theaters, audiences eager to catch a glimpse of battlefields on the mainland and experience the war vicariously as the army advanced down the coast. Within a month of the war, average attendances were hitting upward of 4,000 customers per day, far outstripping the pre-war average. Audiences also had plenty of other incentives to watch news films. If they spotted a relative in the film, they could request for a sukuriin gotaimen – a blow-up of the scene in the film. These were dubbed in the newspapers as ginmaku no saikai (on-screen reunions). News films were also priced attractively. Whereas a trip to the cinema cost 50sen or 1en, a news film cost only 10-20sen, and with the introduction of army-sponsored news film theaters, sometimes even free [7] . | |

The production of news films stepped into full gear in synchrony with the rising popularity of news films. In the first month of the war alone (July 1937) over 2000 reels of news films were submitted to the film censorship bureau [7] .By the end of 1937, an average of 150 news films were being produced a week by the nine major companies: Tokyo-Osaka Mainichi News, Tokyo-Osaka Asahi News, Yomiuri News, Houchi Talkie, United Alliance News, Paramount News, Soviet Special Report, Tokyo Nichinichi’s Sekai no ugoki and Tokyo Asahi’s World Report [9]. A report on news film in Kinema Junpo in December 1937 remarked that “just as audiences’ appetite for such films has grown at a ferocious pace, the need for news films has rapidly multiplied.” [10] | |

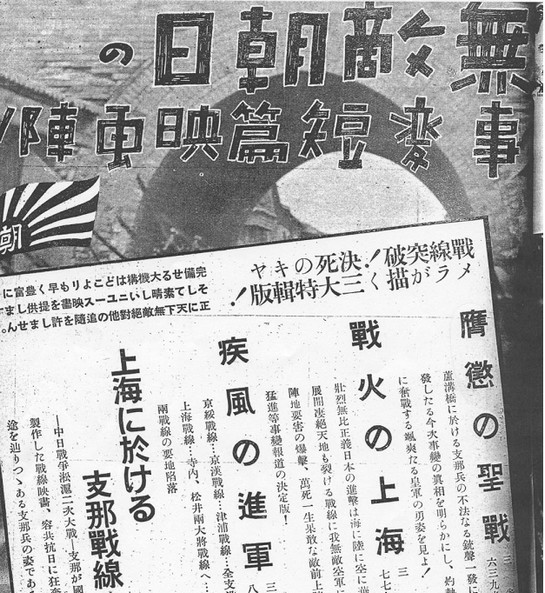

| “The unrivalled Asahi News” advertises its short film releases (Kinema Junpo, January 1938) | |

The distribution of news film also expanded rapidly. Within the first month of the war, a flurry of new contracts were signed between news companies and theater owners as the former sought to expand viewing audiences and the latter sought to guarantee their supply of news films. Tokyo Nichinichi signed a “lightning agreement” with Shochiku’s theater department on July 13th that assured Tokyo’s Shochiku News Cinema would only screen their films. Within a few months, the number of news film theaters had reached an all-time high, with over 1000 theaters around the country screening news films. In a commentary on the the “news film fever” created by the China Incident, Matsusaki Masao, a film critic wrote “Before the Incident one would be hard-pressed to name even one or two News Film Theaters, but now with one stroke one could hit over sixty theaters.” [11] Japan’s first underground cinema was built especially to screen news films, and by January 1938 there were twenty-three news film-only cinemas in major cities alone (Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto and Kobe) [12] . Many theaters which had previously been struggling with poor ticket sales over the summer of 1937 quickly converted their line-up to screen only news films. | |

For all the popularity of news films, they remained a predominantly urban phenomenon, with the concentration of movie theaters highest in Tokyo and Osaka. Still, the reputation of news film reached far and wide, even in rural areas which lacked the facilities to screen these films. Matsuaki writes of his experience traveling to the countryside just hours away from Tokyo, and encountering a group of enthusiastic villagers “who had heard all about news films, but there was no theater within close distance where they could watch it. Thus, they elected a representative who would travel several hours to Tokyo once a week to watch news films, and then share what he watched with his village when he returned. Their inability to watch their loved ones in battle and the sincerity of their words moved me to tears…. Imagine this unfortunate situation replicated in Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Chiba, Saitama! The ones who contribute the most troops to the front line are those from the countryside, yet they reap the least benefits”. [13] | Shaping Public Perceptions The popularity of news film rose in tandem with public interest in the war. Audiences flocked to cinemas to experience the war vicariously, and news films in turn offered an unparalleled patriotic experience. What were the elements of this patriotic experience? An analysis of the films of three major companies – Yomiuri, Asahi and Tonichi-Daimai – during this period suggests that films were carefully edited around three main themes: the difficulty of battle, advancing troops, and eventual victory. The average news film was thirty minutes in length, comprising five to six news clips. News clips were generally short, from one to five minutes, although occasionally news specials would be produced based on a single theme. The quality of news films, from the camerawork to the editing, is remarkable considering the short production cycles that news editors had to work with. Each news clip began with the main headline, proceeding with interspersed rapid-fire commentary on how the Japanese army had advanced day-by-day. The centre of attention in most of the news clips was placed overwhelmingly on the military and its teamwork, with repeated scenes of troop battalions advancing across all manner of natural obstacles, from rivers to ditches. |

Unlike news film produced in China during the same period, which often emphasized the struggle of the individual soldier, in Japanese news film the individual received almost no attention, the emphasis placed on the coordination of entire battalions of troops advancing [14] . These troop scenes would often be interspersed with gunfire and explosion scenes, alternating between the city and the countryside. Most of the sounds however, were carefully orchestrated in the editing studios – although on-site recording for news films was available, the cost was high and the quality low, and for most of the news films the sound of bombs falling, gunfire and troops marching came from stock recordings in Tokyo sound libraries. The audience was none the wiser. | |

Nearly 95% of all news film titles produced in the first year of the war contained the word “Shina” or some aspect related to China [15] . Even so, there was hardly any visual or verbal reference to China, or Chinese people in news films. The war could have been taking place anywhere, had it not been for occasional visual markers like the Bund in Shanghai. If one were to judge from the news films alone, Japan’s army was fighting an invisible “enemy” whose existence was apparent only from mysterious gunfire and explosions. Very rarely did Chinese people appear in Japanese news films; those who did were either waving white flags or the Japanese flag. Whether this was out of coercion or free will is not stated, but their faces were often unsmiling and spoke of fear and helplessness. But to unsuspecting audiences, news films told the tale of a victorious Japanese army crusading against an enemy which lurked beyond the horizon and in the shadows, winning hard-fought battles in lands full of flag-waving welcoming villagers and townsfolk. | |

Despite appearing to be in the pink of health, the news film industry was in fact, starting to founder by the end of 1937. It faced increasing criticism about its superficial coverage on the war, partly attributable to its technique of condensing events into short digestible newsbites. An article in Nihon Eiga in the spring of 1938 was strongly critical of the industry, arguing that it glossed over the war without explaining the motives and justification for the Japanese Army’s actions [16]. In addition, the rising costs of keeping up to date with the war in a foreign country, as well as fierce competition within the industry, soon began to catch up with news film companies. A zadankai (discussion meeting) between the Ministry of Culture, the military and the film industry revealed the true health of news film production; despite a steady flow of revenues it was becoming increasingly difficult to stay profitable, and many news film companies began requesting for government financing [17] . Ultimately though, it would be factors beyond its control that weakened the power of news film – and led to eventual consolidation in the industry.

| Landscape OverexposureProduction Bumps and Handicaps News films on the war in China were informative, entertaining, and a novelty to the Japanese public. But as the war moved inland, the inflexibility of the production cycle and standard format of news films made it increasingly difficult for cameramen and producers to replicate the patriotic experience that had drawn audiences in droves to the theaters. News films had traditionally placed the center of action on the troops, and were edited along the lines of “struggle, advance and victory”. It was a strategy which worked well when the Japanese Army was winning swift battles, but tanked when advancing into China’s inner provinces became an increasingly (and literally so) uphill battle. |

News films, together with other media forms like war movies, newspapers and radio broadcasts, were heavily monitored and weighed in upon to supply the Japanese public with the ultimate “patriotic experience” and drum up support for the war. They were immensely successful at first, providing audiences with the whole deal – auditory, visual, and sensual experience of the war on a distant shore. News films held audiences in their grip as they followed the Japanese Army down the Chinese coast. The swift advance of the troops generated headline after headline for the news industry, launching the news film industry into full gear. By December 1937, Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing – China's three most prominent cities – had tumbled one after another into Japanese control, less than six months after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident [18] . The mood back home was euphoric, and news films stoked this climate with their exuberant headlines: “Hats off Nanjing warriors”; “Occupying Wusong town, Onward we attack!” But there remained a sense of distance between audiences at home and soldiers at the frontline. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the majority of troops were primarily from farming or working classes in the countryside, whereas viewers of news films were predominantly urban. It would be several more years before total mobilization for war had swept up every member of the household in preparation for an attack on the homeland – it may have been war on the continent, but peacetime society back home – crowds were still swarming theaters to experience the visual spectacle of a distant war in a foreign land. | |

In fact, the war was not formally called a war until the end of 1937. Disagreement between the cabinet and the military added uncertainty to how long the invasion would last and where it would extend to. Accordingly, the naming of the war took several permutations. Initial news reports called the war the Northern China Incident ("Hokushi Jihen"), the frontline was known as the Northern Chinese Battleline ("Kahoku Zensen"). By the time the war reached Shanghai however, news films began using the names of Chinese cities in their marketing, partly because of their exoticism, at the same time because they were more familiar to the general public. News films with titles like "The Chinese Frontline in Shanghai" and "Shanghai in the flames of war" began appearing in print advertisements in magazines and newspapers. Shanghai set the precedent for identifying battles by the city's name, so even when the war turned inland and the cities became more obscure, the practice of titling news films according to the name of the nearest city continued: from Nanjing to Wuhan and later Chongqing (where Chiang Kai Shek moved the Nationalist government), as well as Nanchang, Canton, Hong Kong and Hainan in the South. It was not just the major cities, but small towns and regions that were featured in news films – names of towns like Wusong (present-day Suzhou), regions like Zhejiang as well as geographical features like the Yellow river [19] . Through the naming of news films – and in synchrony with other forms of mass media – the Japanese public began to be intimately acquainted with China’s geography and visual landscape. | |

While on one hand appearing to teach audiences about China, in reality the focus of news films was always on the troops, with little attention given to the occupied land or people. The storyline did not veer far from the standard theme – victory after overcoming adversity. Partly, this was a nod to the censors by concentrating on the central task they had been given, to rouse patriotic feelings through the films. But equally important, the production cycle made it impossible for news films to be presented in any other format. Because time was of the essence, the turnover period between shooting the film and screening it was extremely constrained. On average, films were processed, edited, and submitted to the censors within two to three days after the film had arrived from the battlefront [20] . The punishing production cycle which initially was the reason for news films' success would eventually become its liability. | As the war dragged on, it became increasingly difficult for news films to develop new and interesting content. This was because so much of their content was so closely tied to the progress of the troops. On the frontlines, freedom of movement for the press corps was limited; cameramen were virtual appendages of the troops. News cameramen lived and moved with the troops from battle to battle, so much that they became a part of the troops, and the footage they captured also reflected this coexistence. News films even produced self-referential documentaries on their courageous role in reporting on the war. Asahi produced a 33 minute special titled Reporting warriors – A record of the Asahi News correspondents in the Sino-Japanese War, which filmed how news reporters and cameramen had to live with the troops and adopt the same daily routines, for example how the soldiers craving for a bath, built their own bathing facilities in the jungle. It also included a fast-paced series of scenes of a reel of film being transported by a courier running to the car, with the car speeding off in a trail of dust, before being passed to a waiting pilot in a plane titled "Shinpu" or "Kamikaze" that takes off immediately. Clearly, news films were well aware of the importance of speed, and their self-important role as news couriers between the military and the public. The advance of the soldiers and their movement became the central foreground and unchanging focus for news cameramen. It was the one constant in news film in the early months of 1938. This worked out fine, as long as the troops were advancing. But there was one variable which news films had little control over – that was the landscape. If the troops were advancing quickly, the montage of quickly shifting scenery gave the impression of rapid progress. As the soldiers got increasingly bogged down in the war inland however, advance and victory became increasingly difficult to report, or create. Wuhan, the next major city in the Japanese Army’s gameplan, and an important gateway to inland China, was captured in November 1938, nearly a year after the Nanjing government had fallen and some six months after the media had begun prophesying its capture. By then, the once-exhuberant battlecry “To Wuhan!” had become stale, the voices weary. From Coast to Inland But it was the landscape that gave the lie to the carefully crafted image of the victorious Japanese military, and handicapped the patriotic film experience news films were supposed to create. In the initial days of the war, scenes of burning roofs, naval ships docking at harbour, and of populated towns and villages were used to portray the battle for Shanghai and Nanjing. Even when it was impossible to bring back city shots because the troops had not yet entered, editors resorted to other means to convey the familiarity of battle in these two major Chinese cities. |

Shanghai under War -The Second Shanghai Incident [21] (Asahi News, late August 1937), a 30-minute special on the battle of Shanghai, appealed to patriotic sentiment with a 7-minute sequence of harried refugees escaping the city on ships bound for home interspersed with scenes of burning roofs in the countryside, followed by footage of the navy’s resplendent warships in the Yangtze river unloading tanks, trucks and horses into the harbour. Another news film on the battle for Shanghai, a 20 minute short film titled Shanghai Frontline (Asahi News, filmed on September 9th 1937), remarkably had no shots of the city itself as it had not yet fallen under Japanese control. Instead, to recreate the sense of an urban battle, they showed scenes of pitched fighting in the streets from house to house, the aerial bombing of Nanjing by planes that had taken off from ships in the East China Sea, as well as an extended sequence featuring action-packed footage from the siege of Baoshan castle north of Shanghai, which was won only after a dramatic siege. In Nanjing, where a blanket ban on filming had been imposed after mass killing of civilians started, news films contented themselves with reporting on the aftermath of its capture, with long, no-cut scenes of General Matsui’s victory march through Nanjing’s city gate. These scenes of victory over China’s two most well-known cities cemented the public’s belief in the military’s remarkable success on the mainland. | For a brief few months during the spring of 1938, the number of news films on the war declined as the tempo of the war slowed. The fate and future direction of the war was being fought over within the government and military back home. Meanwhile, the army had begun on a series of sporadic surges into inner China. But tight news censorship and a ban on foreign news sources ensured that only positive news of the war filtered back to Japan. News films were diligent in playing their part of portraying the hardship, advance, and victory of the military, and representing the war in a patriotic manner. |

But as the troops advanced inland, “victory” became a decidedly hard sell. After the fall of Nanjing, the Japanese army began sporadic, unsuccessful incursions into Shandong and Shanxi provinces, but this went largely unreported [22] . Meanwhile, the few successful conquests that had been made were duly blown up onto the big screen as news films. Anqing (Anhui province) a port-city on the Yangtze river, was captured in the middle of June 1938, as well as Kaifeng (Henan province), the ancient Chinese capital; both victories were duly turned into news films [23]. On June 12, Chiang Kai Shek’s army, fleeing Kaifeng, destroyed the dikes on the Yellow River, which stymied the advancing Japanese army but also killed Chinese civilians. In news film lingo, this translated into “The treacherous Chinese army’s wild move creates tragedy in the Yellow River” [24]. According to the American ambassador to Japan then, Joseph Grew, “Of course no word of any Japanese setbacks is ever allowed to appear in the local press, but when we read that the Japanese have occupied a certain town, and when several weeks later we again read that the same town has been occupied, it is not difficult to draw conclusions.” [25] | |

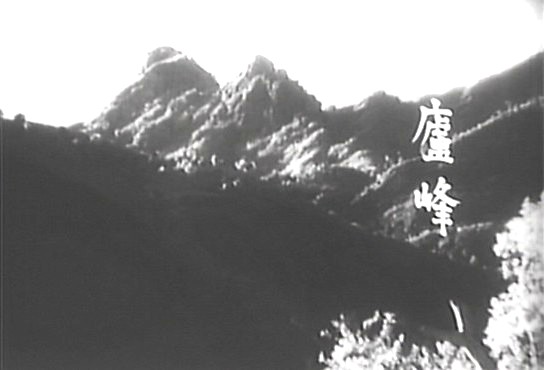

| This scene of craggy peaks was characteristic of the undulating terrain that the troops faced in inland China . Unfamiliar and foreign to Japanese audiences, the difficulty of the battle for Wuhan was emphasized by foreboding images of the landscape. (image from "Fighting Soldiers", Toho 1939) | On June 15, the military declared war on Wuhan, calling this the start of a “long-term holy war”. It would take almost half-a-year before this major city at the crossroads of the Yangste river capitulated, by which time the easy battles of the eastern seaboard had become a distant memory. On the coast, the landscape had been mostly flat, with Shanghai and Nanjing both situated in river basins. Heading upstream however, the sea-level cityscapes soon gave way to hilly, mountainous terrain. No longer could cameramen take quick shots of hand-to-hand combat in the streets, steady shots of smoldering ruins or confident, sweeping city panoramas. Instead, the films show the troops struggling to maneuver over the new terrain – at times scaling the hills with ease, other times clambering laboriously, and at almost all times, being fired at from a disadvantageous position with little cover from the enemy. To Hanko! The Great Advance (Tonichi Daimai, 1938), one of many news films produced over the six-month battle for Wuhan, featured the dramatic battle fought at Mahuiling, located at an important three-way junction of the Yangtse river, and flanked on all sides by mountainous terrain. In the film, the mountains loom large and unfriendly over the viewer, the cameramen himself seems almost in awe and stunned by the scenery which dwarfs the troops in comparison. Another news film, Threatening the fate of Wuhan (Asahi News, October 1938), starts with a shot of the rudder of a warship churning through the waves as it heads up the Yangtse river, and transitions to footage of fighter planes dropping bombs in the distance. The next scene is a face-on shot of the head of a missile, which is then fired, the film cuts to a line of soldiers manually carrying the missiles up the rocky, mountainous slope, a dangerous climb even without the extra load. A common characterization throughout all the news films covering the Wuhan battle is the primitiveness of warfare – the narrow valleys and treacherous mountain terrain made it impossible for tanks to pass or for warships to sail up the river without being ambushed. Instead, thousands of horses were harnessed to navigate the way – but clearly insufficient, many of the troops had to trudge on on foot. And in most of the battles, the enemy was invisible – not even concealed within buildings, but in the far end of the horizon concealed in the mountains, present only through the ceaseless enemy fire directed towards the screen. When Wuhan finally fell on November 15, five months after full-out battle had been declared, the troops arrived in the city depleted and exhausted. Their low morale – and the weariness of the news cameramen and correspondents - betrayed the cheerful coating that news films tried to impose with their positive titles such as Peace Dawns on Wuhan (Asahi News, November 1938). Reporting on this long, drawn-out battle had been costly and exhausting for the news companies. The war in inland China only got more difficult, by which time the attention of audiences had turned elsewhere. The capture of Wuhan spelt stalemate for the war in China and the beginning of consolidation in the cities on the eastern coast. It had been a costly, drawn out, and exhausting battle, transmitted clearly through the foreboding and ominous landscape in the news films. Unintentionally, news films had been betrayed by their own efforts.

The End of News Film Beckons

|

Shortly after, the government stepped in and introduced dramatic change in the news film industry. As early as November 1937, Ito Fukuo from Tokyo Nichi Nichi News film had remonstrated to officials from the Home Ministry and Culture Ministry about the financial cost and tough competition in the news film industry [26]. The response went beyond what they had requested for. On April 5th 1939, the Film Law was passed, establishing what the military had been urging for years – tight controls on the content of all films at every stage, from script approval, to planning, filming, editing and screening. Films with even the slightest hint of criticism of the war, the military or the emperor were rejected. The screening of news films and documentaries on the war was made compulsory at all theaters, at military theaters these were free to the public. A year later, in April 1940, all the news film companies were extinguished in one fell swoop, and consolidated to form the Nippon News Film Company, which was now in charge of scripting and producing all news films. It was the eve of the Pacific War and the beginning of total mobilisation for war. The end had come for a vibrant industry that had once captured the hearts of the public, but like the troops could not extricate itself from the bog of war in inland China.

| Recreating RealismGroping in the Dark The early success of news films, produced by the major newspaper companies, stole the thunder from the major film studios (Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and the newly formed Toho) who were left grasping in the dark for a hit war movie. Unlike the newspaper companies, who had swiftly put in place a well-oiled machinery to create patriotic news films that allowed audiences to vicariously experience the war, fiction films were left scrambling to find their own niche. They were handicapped by their inability to offer the same level of realism as news films. But this distance from reality would eventually turn into an advantage, as it allowed them a much broader canvas on which to imagine the war. This chapter examines three hit war movies from 1938, 1939 and 1940, and analyses their treatment of the war, the mainland, the troops, and Chinese soldiers and refugees. |

Film studios’ first shot in the battle for dominance at the cinemas was to recycle staid material from earlier war films. They floundered miserably. Human Bullet Reporters (Shinkou Kinema, 1937), released two months after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, was a mish-mash combination of old and new. Nikudan, or human bullets, was a theme recycled from the "Human Bullet Patriots" fever of the 1933 Shanghai Incident, where three young soldiers died while planting bombs in an assault on the Chinese troops defences and became national martyrs. The focus on news reporters cashed in on the popularity of news films; even news films themselves had started to make documentaries about their own correspondents. The first wave of war movies tanked. At a hurriedly convened meeting of film studios at the end of 1937, executives moaned the lack of a decent war movie hit. Calling such movies "seasonal fruit" and "crudely produced military items", they blamed the long production time for fiction films – most of the films released till then had been planned before the war – and one executive even suggested "perhaps it may not be possible during the war" for a true war film that captures the heart to emerge. [27] | Imitating Shina in the Studios

|

They would not have to wait long. By the first week of 1938, the war hit that had been prayed for descended on theatres. Five Scouts (Nikkatsu, 1938) focused on the esprit de corps and camaraderie of a company of soldiers resting in a deserted hamlet in the Chinese countryside. The film borrowed heavily from the realistic style and composition of news film. The scene opens with the ruins of a Chinese-style brick gate, on top of which two soldiers are planting the Japanese flag. The scene cuts to the company of soldiers below the gate, who are standing at attention to the flag while a trumpeter plays Kimigayo [28] . The camera slowly pans back upward to the gate, on top of which the two soldiers remain on patrol while the flag flutters in the wind. The use of the brick gate – which to the Japanese public was distinctly Chinese – left no doubt as to the location of this film, and was also a common feature of news films. The planting of the flag, as well as the slow, upward pan towards the patrolling soldiers on guard above, was another leaf taken from news films – A New Dawn Falls on Northern Shina and Shanghai (Tokyo Mainichi News, September 1937), for example, was one of several news films which had used this scene to great effect to symbolise the new era the Japanese occupation had ushered in. | Five Scouts was heralded for its warm, patriotic depiction of the soldiers shared lives, winning Kinema Junpo's Best One movie award in 1938. It celebrates the kinship and brotherhood of the soldiers, who work and live together like family. They share a cigarette, dress each other's wounds and prepare dinner together. The storyline was based on an actual story which had been reported in the newspapers in July 1937, but was radically simplified by the scriptwriter, Aramaki Yoshiro. Five of the soldiers are sent on a scouting mission near a Chinese base camp. There, they are spotted and come under enemy fire. One of the five, Private Kiguchi, is lost on the way back. Day turns to night and rain starts pouring, but Kiguchi still has not returned to camp. The entire company mourns his absence like a bereaved lover. Private Nagano frets, "He's getting wet in this rain." Private Nakamura, who has grieved quietly in the background, suddenly bursts out with passion, "Kiguchi, if you're alive, come back! If you're dead, that's fine too. I just want to know for sure. We won't be able to take it if you're alive and suffering!" Unable to sleep without their comrade, they decide to look for him in the stormy night, but are told off by their commander Okuda, who praises their love for their comrade but reminds them, "this is a battleground. We cannot afford to lose any more troops." Reluctantly, they retreat, with Nakamura almost in tears. But just before dawn arrives the rain stops and a fatigued and Kiguchi stumbles back into the camp. The soldiers rejoice. This sentimental portrayal of the brotherly love between the soldiers and their patriotism and devotion to the emperor won praise and critical acclaim from all quarters. |

Five Scouts was filmed entirely in the studios, its material drawn extensively from wartime stories printed in the newspapers and images from news film. According to Tasaka, "I had no experience of the war, and had to resort to combing newspapers to get a sense of the wartime reality. I used that as the skeleton of the film, and painstakingly gathered other materials to come up with a script." [29] But while the background closely mimics the images of Chinese landscape as portrayed in news film and in the newspapers, by comparison it is clearly only an imitation. The long, pan shots which news films used to great effect to convey the vastness of the continent lack depth of field and sense of reality. Its soldiers are too clean – even after having marched for hours on end through the parched land or fleeing through sorghum fields after being attacked by the Chinese troops, they emerged unscathed, their leaves of camouflage untouched. Just like in news films, there are repeated shots of visual symbols that appeared Chinese, such as bridges and gates made of stone or brick, but with one major difference: the bridges in the movie were far too intact. Chiang Kai Shek's army often destroyed bridges upon retreating into the inland - thus it was rare that news films were able to film an intact bridge. Instead, they often focused on scenes of soldiers hauling lumber to rebuild bridges left in ruins, or simply crossing the currents on horses or man-made rafts. | |

| Mud and Soldiers - Where the hell are we? And what in the world are we doing here? | Shooting On Location |

Riding on the success of Five Scouts, the director Tasaka Tomotaka was able to visit actual battle grounds on the mainland in September 1938 in preparation for his new movie. The few months he spent with the troops at the frontline dramatically changed his impression of the troops, the war, and the mainland changed, and compelled him to rethink his next movie, Mud and Soldiers (Nikkatsu, 1939). The film’s storyline was based on a similarly titled book by Hino Asahei, Barley and Soldiers, a bestselling war diary by a military press officer which recounted the minutiae of the soldiers’ daily lives in a matter-of-fact, reportage style. Tasaka recounted several years later the difficulty in rendering the story into a film after visiting the continent: "While we knew we would be basing our script on Hino's work, we had no idea how to bring this to life at the actual battlegrounds. Anyway, we went there with a blank sheet. But even after going there we found ourselves unable to say with confidence, "Yes this is it [how he would film it]" [30]. At a zadankai in 1939, he told Ozu Yasujirou, "After we arrived, we discovered that our script had to be completely redone. Our experience there caused us to reevaluate our criteria and the thought of turning it all into a film filled us with dread." [31] | Like its predecessor, Mud and Soldiers received critical acclaim for its realistic portrayal of the troops. But there was one crucial difference – Tasaka was able to film most of the movie on location, at actual battlefields right outside Shanghai. The same marching scenes are repeated here, but the scale is amplified. The film features long, extended scenes of hundreds of troops marching across the vast landscape into the horizon, just like in news films. Its narrative follows the advance of a band of soldiers in the countryside, but the impression of the war and the mainland conveyed is much subtler and complex than in Five Scouts. In stark contrast to both its predecessor and Hino’s novel, the overwhelming emotion conveyed in the film is a sense of numbness and exhaustion from the difficult, bogged down war. The film’s leit motif is the rhythm of boots trudging through knee-high sludge in the rain, and the footprints left in the mud. Rain in Five Scouts is a metaphor for the soldier's grief and their love for their comrade; here it speaks of their frustration and exhaustion. Instead of barren land – which was more common in inland provinces in the North like Henan, where the Japanese Army was not very successful – the landscape in Mud and Soldiers is full of swamps, rivers and muddy fields, that were more common in the south and on the coast. The troops advance on foot and horse, a reminder of the laboriousness of warfare on the mainland despite Japan’s far superior military capabilities. When the soldiers pause for a break, beads of sweat drip from their cheeks, and they appear lost in their thoughts. The only time one of them speaks, it is to express his frustration at the war: “Where the hell are we? And what in the world are we doing here?” Five Scouts records the soldiers' group activities in rich detail, but in Mud and Soldiers the camera focused on simple, individual acts of boredom, such as a soldier picking at his nails. The soldiers are mostly mute from exhaustion and make no attempt at small talk, whereas in Five Scouts there are many scenes where the soldiers engage in frivolous conversation such as "how is the moon tonight?" The wounded and injured are left behind as the army leaves camp to move forward for the next attack, in Five Scouts the soldiers had the luxury of staying behind to recuperate. Progress is no longer smooth sailing ahead, instead, every step forward is resisted by the earth. Changes were also made to the portrayal of Chinese troops and villagers. In Five Scouts, the only Chinese representatives are the battalion of "twenty-over" soldiers guarding the village where the scouting platoon is sent to survey. We do not see their faces, they are either concealed in the bunker or part of a blurry mass of soldiers patrolling the area. They are portrayed as an inept and faceless enemy – they far outnumber the five scouts, yet are unable to shoot any of them down and one even perishes in the gun battle. With Mud and Soldiers however, the portrayal of Chinese soldiers and refugees became more nuanced. Suyama Tetsu, one of the scriptwriters, recounted that while Tasaka left them on their own to write the script for most part, he repeatedly emphasised that they should "portray the Chinese masses with humanism and empathy", making them revise their script several times until he was satisfied. The movie boasts the requisite scene of a Japanese soldier helping an innocent civilian – such as when the soldiers discover an abandoned baby and wrap him in a blanket. But it was the movie’s depiction of the enemy soldiers that was unusual for its time. In the prolongued gunbattle scene that forms the centrepiece of the movie’s second half, we see soldiers and refugees fleeing from the village under attack – a gentle reminder of the civilian damage the war had caused. When the troops enter the village, the camera briefly lingers on the corpses of Chinese soldiers in a bunker, and focuses on the fear in the eyes of one who is barely alive. It was an invitation to audiences to consider the perspective of the soldiers on the other side who had sought to defend the village. Towards Long-term War By the end of 1939, it was clear that the end of the war in China was not yet in sight, despite what the swift victories on the coast two years earlier had suggested. Mud and Soldiers was a product of this changed climate. On the surface, it differs little from earlier war films, and includes the requisite patriotic scenes such as soldiers crying out “Long live the emperor!”, and Japanese soldiers’ kind acts towards the Chinese. But it was radically different in portraying the war as a long, intractable battle which had not yet been won. After the capture of the village, the soldiers march off into the horizon, heading bravely to their next destination. According to the script, they appear “calm and stoic, strong, courageous, and beautiful.” This played into the military’s gamble to prepare the public for a long-term war that required their total participation. In addition, the film also differed in its representation of the Chinese soldiers as human and entirely competent. This was a convenient explanation for why progress on the warfront had slowed – the enemy’s calibre had improved. But still, the Japanese army would persevere. |

Legend of Tank Commander Nishizumi (Shochiku, 1940), was one of the most popular war movies, and can be considered the equivalent of today’s action flick. The movie was based on the real-life story of Nishizumi Kojiro, which had been popularised by Kikuchi Kan, who wrote a series of columns on his life in Mainichi News. Kikuchi, along with Noda Kogo, the movie’s scriptwriter, and the illustrator Ihara Usaburo, had been one of several “pen battalions” dispatched to the mainland to translate the war into stories, illustrations and movies easily digestible by the Japanese public. Noda recalled that upon reaching Shanghai, “the smell of gunpowder had not yet disappeared and the outskirts of the city was still lined with unexploded grenades and sun-bleached bones. We would occasionally hear the sound of gunfire from retreating soldiers in the distance.” [32] This was more than a year after the Japanese army had occupied the city. The mood of ferocious, bloody fighting was transferred on screen, with dramatic images of entire villages and towns on fire, and every battle scene showing heavy casualties on both sides. One soldier notes that the war may have to carry on for another five or six years. Another chips in, “the battle has only just begun.” | Moving away from the pseudo-objective news reportage style that had been favoured by directors like Tasaka, Nishizumi developed a new, fast-paced, action-based style for war movies. As a “legend”, it could afford to pay less attention to reality and more to entertainment value. While the leit motif for Mud and Soldiers was the boots of soldiers trudging through mud, here it was surely the caterpillar treads of the tank cold-bloodedly devouring the earth and all that crossed its path. Nishizumi was a paean to the power and might of the tank and the mechanisation of war. But in reality, while tanks had been used in battles on the coast, they proved useless inland when the troops had to navigate craggy mountain passes and cross vast rivers. |

As was necessary for all war films of the era, Nishizumi features the requisite “baby scene”, where the soldiers come across a wounded Chinese woman with her baby in a barn. She recoils in fear when the soldiers approach. But a soldier speaks in Mandarin, “We are your good friends. Don’t be scared.” A Japanese doctor tends to her wounds. But in the night, she escapes, leaving her baby who has inexplicably died in the night. The next morning, the men dig a grave and build a mini-altar for the “little nameless one”. According to the film historian Peter High, this was the only patriotic scene left over from Noda’s script, which was dramatically changed by the director Yoshimura. The original script included racist depictions of Chinese soldiers as inept sitting ducks. These were excised in the movie, which features the enemy as “worthy adversaries”, who fight man to man in every battle, and in the end succeed in taking Nishizumi’s life. High argues that this adds a “majesty and pathos” to the movie that is lacking in other war films, but that this creates a disharmonious contrast with the other standard patriotic scenes. [33] | Five Scouts, Mud and Soldiers, and Legend of Tank Commander Nishizumi each adopted unique interpretations of the war, and each was critically acclaimed in the local media. Five Scouts, the earliest to be produced and rushed out by Nikkatsu in an attempt to stem the tide of news films, saw the war as a celebration of the soldiers’ patriotism and esprit de corps. It attempted to borrow realist features from news films, but constrained by the limits of studio film-making, was unable to portray the gritty nature of actual combat. The movie’s simplified story also allowed it to fall easily into a “us versus them” ideology, dehumanizing the enemy troops. Mud and Soldiers benefited greatly from Director Tasaka’s experience with the troops on the frontline, and the result was a much more grounded, close-to-earth encounter with the dirt and grind of daily fighting. It also attempted to portray Chinese people and soldiers more humanely, but still does not venture far from standard stereotypes of Chinese and Japanese that the military sought to propagate. Nishizumi was an action flick which scored high on entertainment value but less on the reality score. But in its portrayal of the war as squarely and fiercely contended by both sides, it succeeded in achieving a level of reality that most war movies had fallen short of. Building a road to peaceIn Search of Shina |

In the spring of 1938, Kawakita Nagamasa [34], chairman of Towa Trading Company (then known chiefly as an importer of European films), made the following criticism of cinematic portrayals of the war to date: "In China, they call foreigners waiguoren. But this does not include Japanese. In Japan, the word for foreigner, gaikokujin (the characters in Chinese are identical) probably does not include the Chinese in anybody's mind. Instead, we think of red-haired, blue-eyed Westerners. But in truth, the Japanese don't even understand one-tenth about the Chinese what they do about gaikokujin." [35] Kawakita was one of a minority of film producers and directors displeased with the superficial treatment of the war in the majority of news films and drama films released till then. They put together films that approached the war holistically, and encouraged audiences to reflect on the military’s presence on the mainland and Japan’s relation to China and its neighbours. In this chapter and the next, I will examine the works of two key figures in the wartime cinematic world: Kawakita Nagamasa, a film producer, and Kamei Fumio a documentary director and editor. Both sought to create public discourse about the meaning of the war through their films, which offered insights into the mainland that had never been seen in cinemas before, but the films that resulted and the outcomes they reached were entirely different. In answer to his earlier question about Japan’s ignorance of the mainland, Kawakita funded a big-budget production, The Road to Peace in the Pacific (Towa, 1938). It was one of the first real Sino-Japanese productions and the first drama film during the war to break out of the studios and shoot on location in the mainland. The script was written and directed by Japanese but the actors hired were Chinese. In a radical move for a Japanese film, the entire dialogue was in Mandarin, emphasizing that the film's point-of-view would be that of the Chinese side, not the military. To hire its Chinese cast, Towa organized classified advertisements in the Shanghai newspapers. Shanghai, which had a booming film industry prior to the outbreak of war, was full of jobless actors looking for work, and hundreds turned up for the auditions held at the ballroom of a hotel. Although many film industry veterans had fled along with Chiang Kai Shek's army, those without political leanings, or the means to flee to Hong Kong, were stranded in the city. [36] | |

| Slick advertisements reflect the budget and media attention garnered by The Road to Peace in the Pacific. But critics and audiences alike found the film about a Chinese couple too bland and unexciting and it flopped at the box office. | Cultural Exchange on Reels |

Upon its release at the end of March in 1938, newspapers and film magazines were inundated in expensive colour advertisements promoting the film. The movie's main cast, the male lead Xu Chong, and three female actresses Bai Guang, Zhong Qiufang and Li Ming were flown to Tokyo for a press conference with the national media. The publicity that the film generated was part of Kawakita's campaign to nudge the media into providing more balanced coverage of the mainland. But the odds for success were not high: although the fighting had temporarily reached a standstill, there was ferocious debate both in Japan and international circles over the legitimacy, intent, and extent of its invasion of the mainland. Meanwhile, independent-minded branches of the army had started making forays into the inland; it would be a matter of weeks before the military announced the start of "full-scale war" in China. It was in this hostile and tense climate that the Chinese actors landed in Japan for a benign "cultural exchange" with the local media. The three Chinese actresses were complimented on their beauty, and queried about their first-time visit to Japan, shopping at Ginza, as well as Chinese prejudice towards the Japanese, to which Bai Guang answered, "It's a sensitive topic and I don't feel like talking about it." [37] | By focusing on the Chinese point of view, the film represented a radical point of departure from the standard military movie. The storyline revolves around a young Chinese farming couple in Northern China, Zhao Futing and Lan Ying (played by Xu Chong and Bai Guang respectively; the latter would soon become a major mainland star and was later dubbed "the Chinese Mae West). Their simple, pastoral lives are disrupted by the war, and they decide to gather their possessions and flee to the capital, Nanjing. They are unable to head south however because of the fighting, and instead head north to Beijing where Zhao's old friend Wang lives. Zhao and Lan are portrayed as simple folk callously swept up in the war. When they decide to flee, Lan breaks into tears, and cries out, "Why start a war when everything is well. Why fight with China?" To which Zhao answers, "I don't know, who knows." Barely into their journey, they cross the path of a company of Japanese soldiers at the magnificent Yugang Buddhist grottoes near Datong, in Shanxi province. Initially huddling in fear as a Japanese soldier approaches, they break out in smiles as they "discover" the kindness of the Japanese troops who give them a ride to Datong, and share their caramel and tobacco with the couple. Later in Beijing, when the couple's friends express surprise at their encounter with the troops, they nonchalantly dismiss their concern, arguing "It was nothing, they saved us several times and even let us ride on their cars here." Through this "cultural exchange" on wheels, the movie sought to promote goodwill between the two peoples, yet it only scratched the surface by not delving into the reasons for prejudice on both sides, and dismissing them as mere stereotypes. This was a far-too-common problem glossed over in other war films which often had similar “cultural exchange” scenes, except in this case the exchange was in Mandarin, not Japanese. The Bridge Fails |

For all the media buzz that the film created, it was a major disappointment at the box office. It fared no better on the mainland, where it was released a year later. Aiming to be a Sino-Japanese production that built the bridge for peace between both sides, it succeeded in pleasing neither. It lacked the fast-paced drama and action of military films that the Japanese public had come to expect. The average viewer did not have the stamina to sit through nearly two hours of subtitles of a slow-moving film. Critics blasted the film as a bland travelogue, criticizing the long, extensive scenes devoted to famous landmarks that came hand-in-hand with bland political lessons. On their way to Beijing, Zhao and Lan reach the Great Wall's Badaling pass. Lan innocently wonders, "What's this wall?" Upon being told that it was meant to keep out foreigners, she says "But it obviously hasn't been of use, because the Mongolians came, and so have the Japanese." To make the point clear, they are surrounded by Chinese bandits, who are quickly chased away by a passing platoon of Japanese soldiers. "How helpful of the Japanese troops," says Lan in gratitude. When they arrive at Beijing, they tour famous attractions such as the summer palace and Tian Tan with their friends. The Empress Dowager's marble boat inspires criticism of the Western imperial powers who pillaged the nation, and is of course a backhanded compliment to the Japanese army for removing them. And at the movie’s conclusion, as if the message had not been explicit enough, an old Chinese man, Rui Xiang (the father of Zhao's friend Wang Minsheng) launches into a lecture about the need to work together under the Five-Colours flag [38] for the sake of the nation. Peace will start from Northern China, he says. He tells the younger generation seated around him that they need to have take a step back and look further afield, for the Japanese have helped China by defeating the imperial powers, and that Japanese culture will be the spark that inspires China's new era. | The movie's paternalistic attitude won fans from neither Chinese nor Japanese viewers. While aiming to present the view of the occupied, it ended up instead portraying the occupier's views through the occupied. To the Chinese, the movie's pedantic assertions that the Chinese had misunderstood Japanese intentions and that the army was their benevolent saviour merely added insult to injury. While The Road to Peace in the Pacific tried to be a bridge between the two, it ultimately ended up distancing both sides. Of Ruins and refugeesDocumenting Shina – Toho’s City Trilogy |

Kawakita was not the only filmmaker seeking to portray a more authentic China than the hollow images in news films and the caricatures of war films. At the same time that Kawakita and Towa were planning their movie, Toho Film had decided to fund a documentary trilogy introducing China’s three major cities involved in the war, Peking, Shanghai and Nanjing. Toho was a relatively new arrival in the film industry, born of the merger between PCL and its subsidiaries two months after the Shina Incident. It would grow into a major force to be reckoned with, its independent and well-funded documentary unit unparalleled at that time. [39] | |

For the first instalment of its City Trilogy, Toho chose the renowned Miki Shigeru as cameraman, who was known for his camerawork with Mizoguchi Kenji and Itami Mansaku, and Kamei Fumio to edit the footage. Kamei was a promising filmmaker who had already proven himself through two other popular documentary features, Through the Angry Waves and Shina Incident (both released by Toho in 1937). Before Miki went to Shanghai in October, Kamei provided him with a shopping list of appropriate subjects, "scenes appealing to the sentimentality of the Japanese public, things like a red sun at sunset. Miki Shigeru faithfully shot everything on the list." [40] But when Miki returned and screened the six hours of footage he had filmed to Toho officials, there was a moment of stunned silence. Instead of glorious victory, he had captured the ruins of a city scarred with the heavy casualties of war everywhere. The following tale has been repeated many times and mythologised in different ways, but Kamei is said to have stood up and nonchalantly accepted the challenge, saying "It's fine, it's fine, I can work with this." [41] | |

The result, Shanghai (Toho, 1938) was a nuanced and finely detailed documentary which on the surface appeared to be a standard, propaganda film. It came with the requisite patriotic music and narration and heroic footage of the navy, army, and the naval pilots. But there was much more to the movie than meets the eye, as was foreshadowed in the opening scene. The movie opens with the solemn chimes of a clock tower on the Bund, but quickly transitions to a pan of Shanghai's cityscape. The skies are alight with fires and the lingering plumes of smoke from smoldering roofs. We are introduced to the river-borne route that the navy took to attack the city, and shown admiring images of resplendent naval destroyers and planes. Next, we are introduced to Shanghai's major landmarks – famous hotels, consulates, bridges, and financial institutions. Everywhere on the Bund Chinese people are going about their daily lives amidst the naval ships in the background. "There is no sign of fighting, and all looks peaceful," says the voiceover narration. "But just look further ahead, at the Chinese settlements." [42] The movie transitions to clips of anti-Japanese posters, films and finally to the shuttered shophouses and near-deserted ruins and rubble of this part of town which experienced fierce fighting. Indeed, nothing is as it initially seems, as this movie prepares the audience from the start. | Nowhere is this more obvious than in the subtle facial cues and silent gravestones that consistently contradict and undercut the patriotic voiceover that celebrates the occupation of Shanghai. "This is where the Imperial Army fought bravely and came under attack on both sides of the creek by the enemy" – but the screen is littered with spent shells, bones, and gravestone markers that are an affront to the senses and stand testament to the heavy casualties of the war. |

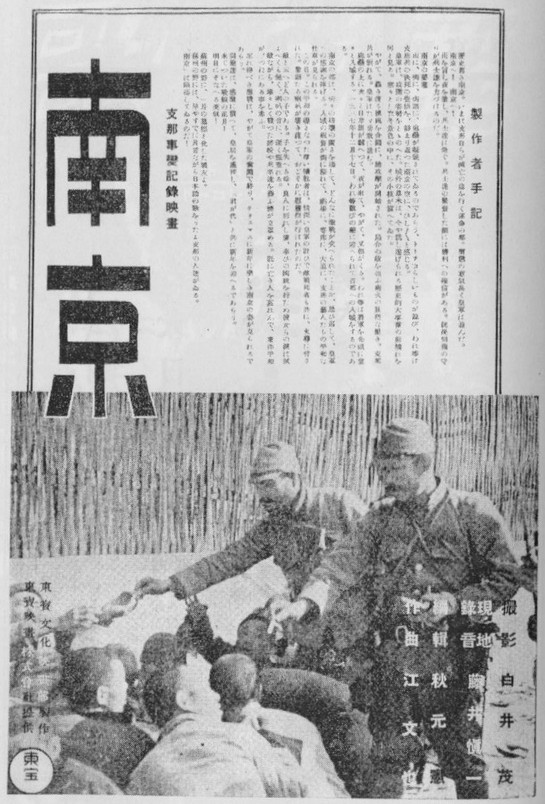

| Nanjing - black and white advertisement from Nihon Eiga advertising. This poster shows a screen capture of soldiers handing out cigarettes to the refugees in a huddle, but while attempting to highlight their benevolence also clearly points out a power hierarchy between the occupier and the occupied. | Nanjing, the second film in the trilogy, was filmed two days after the city’s fall in December 1937 by Shirai Shigeru and edited by Akimoto Ken. It offers an interesting contrast because of the similarity of the images used but the different effects that were achieved. It minced no words about the extent of the destruction – the screen overflows with helmets, spent bullets, unexploded grenades, and all manner of an entirely annihilated city. The movie opens with a slow, wafting shot of a misty swamp, the trees barren of leaves. There is no sign of life, only the sound of the troops marching by. The city is a wasteland. But the introduction is paired oddly with an upbeat, faux Chinese tune that saps the pathos and results in a disconcerting, unreal experience. By comparison, in Shanghai, the long, traveling scenes of destruction in the marshes, the city, and the suburbs are eulogised by the lonely cry of a violin in a minor key, which elicit a keen sense of tragedy. Further, the scenes of destruction in Nanjing only comprise the first few minutes, as if to reduce its significance, whereas in Shanghai it takes up almost ten continuous minutes in the second half. The two films’ different representation of the victory march also merit comparison. The victory march, a standard feature of the patriotic cinema experience, had been used in news films and other documentaries to convey the military’s success. But in Nanjing, it took on additional weight and significance; not only was it Chiang Kai Shek and the Kuomintang Party’s capital, it was a historic capital surrounded on all sides by a series of ancient castle gates that date back to the Ming Dynasty. The gates were designed for defense purposes and were heavily fortified. There were three main gates from which the Japanese army attacked – Yijiang Gate in the west, along the Yangtse river, Heping (or peace) Gate in the north, and the impressive Zhongshan gate in the east, which comprised four rows of seemingly impregnable gates. Their near-complete destruction is featured in the movie’s opening minutes – although the bodies had been removed, the high number of casualties was obvious from the sea of darkened uniforms, helmets, and spent bullets covering the ruins. It was through Zhongshan gate that General Matsui chose to conduct his victory parade. Leading the cavalry, General Matsui’s troops cross the screen in resplendent fashion from right to left, on their way to the Kuomintang headquarters. In the background, Nihon Rikugun (The Japanese Army), a favourite marching tune is played. The same trumpet music is used in Shanghai during the victory parade too – but almost immediately it fades out, and the camera, trailing along and filming the crowd in the opposite direction from the march, reveals the anxious, fearful, and uncomfortable expressions on the Chinese faces in the crowd. In fact, portraying Chinese citizens turned out to be the most difficult, and often gave the lie to the careful image they were trying to construct and maintain. And in many cases scenes of soldiers playing with children appear to be staged or reenacted. In a promotional poster used for Nanjing, two Japanese soldiers are seen giving out cigarettes to Chinese men in the crowd. But a closer look at the poster – and of the scene in the movie – reveals the men cowering along the wall. The two soldiers tower over the trembling men, who had been rounded up for questioning for involvement with Kuomintang activities. The intent of the poster was to highlight the army’s benevolence, instead it was undercut by the visceral fear in the expressions of the men coiled up against the wall. Shanghai too, featured scenes of the army’s civilised and benevolent gestures to the Chinese population, for example of the prisoners-of-war having their meal. But this scene is undercut by the wary eyes and sideway glances at the camera, and their reluctance to pick up their chopsticks and eat the bowl of rice laid before them. In this case however, given Kamei’s refrain, that not all is as it seems, it is much more likely that the contrast was intended. But Shanghai was not edited as an anti-war movie, nor was it seen by one. It had many redeeming scenes, such as footage of the Japanese Settlement, resplendent navy warships and Japanese soldiers playing with children at local schools. But these would repeatedly be undercut by running scenes of grave markers along the road, by the creek, or in the ruins. This delicate juxtaposition of patriotic scenes with grave images of the war allowed Kamei to expose otherwise controversial images of the war that no other newspaper or film dared to screen. Peking was Kamei’s next work, and it showed how his thinking had evolved in the months after Shanghai and Nanjing were released. Filmed in early 1938, when the city was well under Japanese control, it reveals the careful eye of a director acutely attuned to the nuances in a subject’s subtle turns of expression, and its effect on an entire scene’s composition. Unlike the earlier two films in the trilogy, which had been filmed soon after the end of battle, an uneasy calm had settled in the city. Kamei chooses not to portray the Japanese military at all, but focused his lens wholly on the ancient capital and its people. For this reason, and because of its focus on Beijing’s people and landmarks, it was blasted as a tepid travelogue – similar to the criticism that The Road to Peace in the Pacific had faced, yet it lacked the paternalistic attitude and patronizing tone of the latter. As a work of art, Peking is a near-masterpiece. The film went missing after the war, and was only rediscovered in 1991, with the first reel missing. But the remaining reels reveal thoughtful shots of Beijing’s famous landmarks like the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace and Yonghe Temple, as if pausing slowly to contemplate their existence and historic significance - unlike The Road to War in the Pacific, which ran through the same landmarks like a whirlwhind. At an almost lackadaisical pace, Kamei’s camera brings us through Beijing’s streets, showing us the daily lives of hawkers trading their wares, street acrobats performing, rickshaws wending through the crowds and merchants haggling with customers. The voices of peddlers calling out to customers, the sound of clanging pots of the kitchenware dealer, the cling-cling of a hawker selling nails, all combine to form an uncoordinated but perfectly rhythmic and harmonious soundtrack, a musical accompaniment that no other film made during the war can boast. Kamei also makes no attempts to conceal the camera’s presence: there are numerous shots where children, or customers glare into the camera. In one scene of a man sitting on a stool eating buns, the man angrily waves the camera away, shouting, “Don’t film, why are you filming me!” In another scene of young men and women drinking tea under trees, the subtitles read, “What is he filming?” “I heard that the cameraman is Japanese”. |

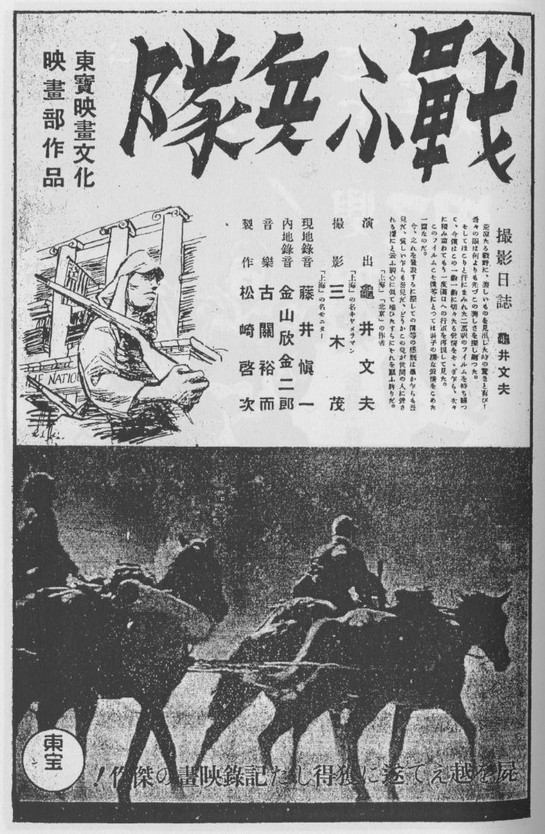

| Fighting Soliders - black and white advertisement from Nihon Eiga advertising | Tired Soldiers But Kamei's real tour de force was to come in 1939, when he was assigned to follow a company of soldiers as they sought to capture Wuhan, a strategic stronghold along the Yangtze river in China's heartland. This was called the battle for Hankou, or Kanko in Japanese. For four months, Kamei and his crew of three others (including Miki Shigeru from Shanghai) lived together with the soldiers and filmed their lives, from the battles in Jiujiang and De-an (Kyuko and Tokuan in Japanese) to their final entrance into Wuhan. The final result, Fighting Soldiers (Toho, 1939), was an empathetic and compassionate record that extended beyond the soldiers in battle to the lives of the thousands of villagers affected. Its opening sequence was unlike any that had been produced before. Against the vast backdrop of barren land, emerges the caption, “The continent is undergoing agonizing spasms of pain for the sake of the birth of the New Order.” The scene transitions into a half-minute close-up of the weathered, grim face of a mustachioed Chinese man gazing solemnly into the camera. The roofs of farmhouses are on fire, and an entire exodus of villagers is evacuating the land. To leave no doubt about the cause of their eviction, the next scene transitions into a close-up of tanks rolling across the parched land, and the Japanese flag fluttering in the wind. In one of many heartbreaking scenes, a pint-sized young boy trods wearily along a long road. In the distance tanks are rolling quickly upon him, and almost in fear, his steps falter, he totters, and falls over himself as he makes way for the tanks to pass. |

Kamei’s empathy went beyond the displaced villagers. The weariness of the soldiers is evident in every step forward they take as they march on; in another wrenching scene we watch the slow, painful collapse of a horse too tired to continue any further. In stark contrast with Nanjing and even Shanghai, the army’s victory march into Wuhan’s central square was infused not with patriotism but war-weariness; every note of Kimigayo ringing hollow as the soldiers stare blankly into space. As argued in "Landscape Overexposure", this was partly because of the vast difference in the battle on the coast and in the inland. In Towa’s trilogy of the coastal cities, the military’s swift victories made it easy to stir up patriotic sentiment. Fighting Soldiers marked Japan’s slide into an intractable war that would eventually prove impossible to win. Kamei himself later reflected, “this was the time when Japan began to slide deep into war, and consequently into the morass of the Pacific War. I kept wishing for the end of the war as I was filming soldiers and Chinese farmers being killed or injured in sacrifice to the war.” [43] | |

Upon its completion, the movie was dubbed by the censors as “Tired Soldiers”. Toho ran a series of advertisements in the weeklies in the spring of 1940 in preparation for its upcoming release. But the political climate which had excused the release of Shanghai and Peking had changed significantly, and the Film Law’s passage in April 1940 tightened the criteria for what was acceptable in a film, including strict rules for representing the military and the emperor with utmost reverence and admiration. Toho received a note from the censors that they should “reconsider” its release, and taking the hint, voluntarily withdrew the film. A year later, Kamei was arrested by the Special Higher Police under the Peace Preservation Law of 1925, accused of stoking “antiwar and pro-Communist sentiments among the general public”. He was held in custody for a year, the only filmmaker to be punished under the Film Law. Years later, in 1977, upon the rediscovery of the film, Kamei wrote that “I hadn’t deliberately set out to film an antiwar movie. I just wanted to portray as simply as possible the war in all its rawness.” [44] But the bell had tolled for the end of realism in war films. From hereon, an entirely different species of film would be necessary to mobilize the public.

| Romanticising ShinaFrom Realism to Romance |

“The Japanese think of the continent in romantic colours, as a sort of paradise. This is the fervour that gave birth to the Continental Trilogy.” [45] - Yamaguchi Yoshiko, formerly known as Ri Koran | Slowly but surely, the film industry had begun moving away from the documentary realism fervour that started with news films and continued with military films like Five Scouts and Mud and Soldiers. Realism was a technique that worked well when the army was charging down the continent’s seaboard. But by the summer of 1938, the military had changed its tack and started selling the war as a “long-term, all-out war”. This would gradually be reflected in film – from the shift in documentary, reportage-style films like Mud and Soldiers to hero-based, romantic films like Legend of Tank Commander Nishizumi, which openly acknowledged that the war “had only just started”. It became easier to create patriotic experiences by viewing the war and the continent through rose-coloured lenses, and discarding the increasingly dreary pictures that news films were bringing back from the war. This aesthetic shift towards romanticism would continue well unto the war’s end, and was a significant lynchpin in the total mobilization of the nation. Gender-based Nationalism |

Here is examined the romanticisation of China, and of Japan’s relationship with China in Toho’s “Continental Trilogy”, comprising Song of the White Orchid (Toho, 1939), Shina Nights (Toho, 1940) and Vow in the Desert (Toho, 1940). Each of the films revolved around the screen romance between the male idol Hasegawa Kazuo and an upcoming “Manchurian” star, Li Xianglan (Ri Koran in Japanese, real name Yamaguchi ). The storyline across the three films was nearly identical. Li, representing the mainland, played the impudent beauty, who upon meeting Hasegawa, representing Japan, falls in love and overcomes her earlier prejudice and misunderstanding of Japan’s benevolent intentions. The gender play was further reinforced by the actors nationalities– Hasegawa the charismatic male Japanese and Li the beautiful Chinese actress who spoke perfect Japanese. But Li Xianglan was really Yamaguchi Yoshiko, the daughter of Fukuoka merchants who had immigrated to Manchuria and was near-fluent in Mandarin. Promoting Li/Yamaguchi as a Manchurian star however, fit perfectly with the studio’s marketing – and made her a role model in the eyes of the authorities. Yamaguchi herself was fully aware of the manipulation of her role in this gender-nationalism battle. As she later wrote in her memoirs, “Japan stood for the strong male, China for the subservient female. If China obeyed Japan, Japan would protect it. This was the hidden message in the films.” [46] | |

The use of gender play to represent nations and political intentions was not new to cinema. The film critic Sato Tadao dubbed these “rashamen” [47] films, “When the occupier wants to convince the occupied to cooperate, he comes up with a pure love story between the two to conceal his attentions. It is a universal archetype.” The relationship between Li and Hasegawa’s onscreen characters has formed the main subject of research into Japanese films about China. Their gender representations need little elaboration. In the box office hit Shina Nights (Toho, 1939), Li plays Guilan, an untamed, impertinent Shanghainese maiden who has lost her family in the fighting. Hasegawa plays Hase, an immaculately groomed naval officer who rescues Guilan from a Japanese man who is harassing her to return some money. Hase persuades the other members at his hotel to take Guilan in, but instead of gratitude she is full of vitriol and hate for the Japanese. Thereby begins the “civilizing” process through which Hase attempts to groom Guilan into a gracious and well-mannered lady, and culminates in the “slap”, whereby Hase, frustrated with Guilan’s rejections, gives her the “whip of love” which brings her to her senses and she awakens to Hase’s good intentions [48]. While this may have fit into Japanese stereotypes at the time, the act of a Japanese man slapping a Chinese woman in order to win her to his side would not, and did not win any hearts or minds on the mainland. As Li/Yamaguchi later pointed out, “the notion of her falling in love with the man represented a humiliation both in terms of the story and in symbolic terms.” And Tsuji Hisakazu, a film censorship officer for the Shanghai Army Propaganda Unit, did his best to prevent the trilogy from being shown in China, “To put it bluntly, the inability to portray the real mind of a Chinese is bound to arouse an unpleasant backlash among audiences there.” [48] | But to Japanese audiences, the love between Li and Hasegawa’s characters expressed their frustration at their rejection by the mainland, and was a metaphor for the cultural exchange that would allow the two sides to understand each other. In Song of the White Orchid, Li Xuexiang (Li Xianglan) leaves Matsumura Koki (Hasegawa Kazuo) because of a misunderstanding, and joins the Chinese side in attacking the Japanese. When the small guerilla group she leads bumps into Matsumura, the two have a confrontation in the hills. “Oh, it’s you,” he mutters angrily, as the two stare at each other. She refuses to speak to him in Japanese. Matsumura, who had patiently taught her the language, challenges her to stop speaking in Mandarin, ”Answer me in Japanese. Why don’t you speak Japanese.” She looks suitably chastised, and answers as he demands in Japanese. He then changes his tone, softly addressing her with the affectionate “kimi” instead of the blunter “omae”, “Now I understand, but why have you become that way? You, who understand Japan so well.” To leave no doubt, she answers “ I was forced to by your heart. “ He scolds her, “throw away your personal feelings. You are no poet”. |

| Shina Nights - Ri Koran "awakens to a man's love" after being slapped by Hasegawa Kazuo | Unconcealed Prejudices |

Yet, behind the romanticisation of China the exotic and China the beautiful, there were subtle contradictions that underlined the black-and-white stereotypes portrayed in the film. The opening scenes where Li and Hasegawa’s characters meet, for example, all revolve around money, and its misappropriation by a Chinese character. In Shina Nights, Hase saves Guilan from a Japanese man demanding money from her which she denies taking, “I’m not that sort of person. I would die before doing something like that.” And in Song of the White Orchid, Li refuses the money that Matsumura offers her for her rickshaw-puller’s injuries, “that’s a terrible habit of Manchurians [extorting money from the Japanese by faking injuries]. Please know we have plenty of good habits too.” As documents from the Japanese army’s occupation period in China revealed, one of the most common reasons cited for mistrust between Japanese and Chinese was over conceptions of money. “Chinese people eat and don’t pay,” complained Japanese shopkeepers, who whined about having to constantly worry about overpaying when shopping. [49] Guilan’s involvement with a money dispute represented Japanese fears at being duped by the Chinese, but the delineation of the plot seems to suggest that anxiety is unfounded. And in Song of the White Orchid, Li’s decency in refusing money that she feels inappropriate signals that not all Chinese accept money without principals. Needless to say, this was also intended as an edifying portrayal of how the ideal Chinese person should behave with regards to monetary transactions. | |